Valve Replacement

The aortic valve and the mitral valve are the most commonly replaced valves. Pulmonary and tricuspid valve replacements are fairly uncommon in adults.

Replacing a narrowed valve:

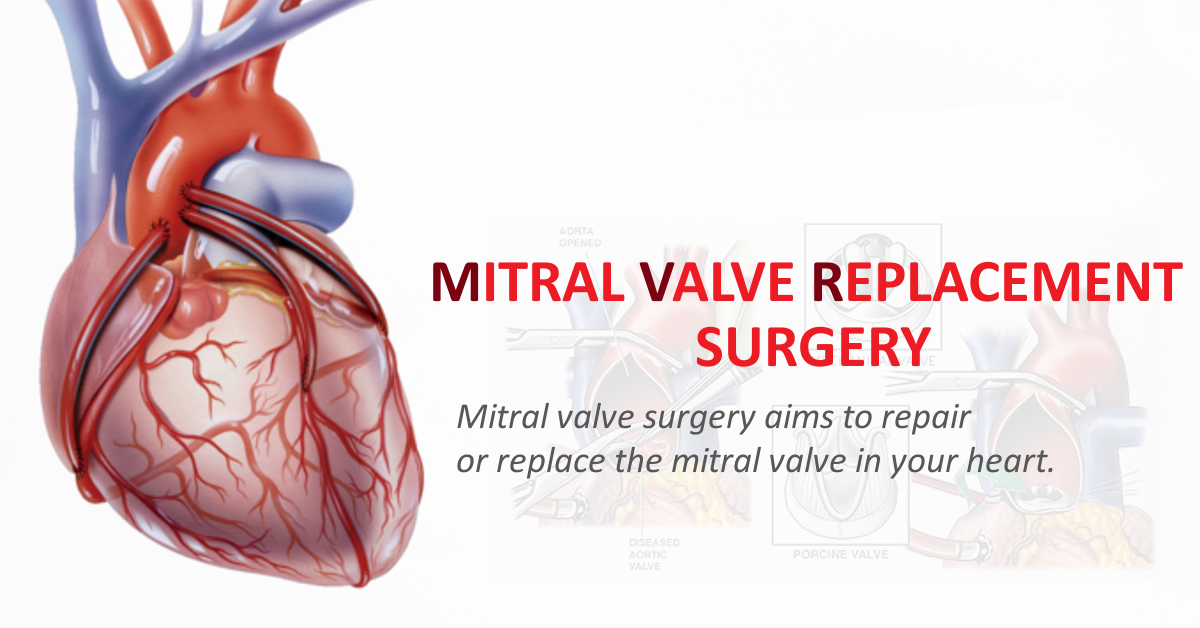

The most common valve surgical procedure is aortic valve replacement for aortic stenosis, or narrowing of the aortic valve. Mitral stenosis is another condition that sometimes requires a valve replacement procedure.

Replacing a leaky valve: Aortic regurgitation, (sometimes referred to as aortic insufficiency) is another common valve problem that may require valve replacement. Regurgitation means that the valve allows blood to return back through the valve and into the heart instead of moving it forward and out to the body. Aortic regurgitation can eventually lead to heart failure.

Mitral regurgitation may also require a valve replacement. In this condition, the mitral valve allows oxygenated blood to flow backwards into the lungs instead of continuing through the heart as it should. People with this condition may experience shortness of breath, irregular heartbeats and chest pain.

Surgical options for valve replacement include:

- Mechanical valve — a long-lasting valve made of durable materials

- Tissue valve (which may include human or animal donor tissue)

- Ross Procedure — “Borrowing” your healthy valve and moving it into the position of the damaged valve aortic valve

- TAVI/TAVR procedure — Transcatheter aortic valve replacement

- Newer surgery options

Many people are able to go on to live a full and healthy life.

Mitral valve repair can often provide a very normal life to the patient without the need for ongoing blood thinners and other modifications associated with valve replacements.

Aortic valve replacement is more likely to require ongoing medication, but any one person’s post-operative medication will depend on that person’s condition and risk factors.

The operation will be scheduled at a time that is best for you and your surgeon, except in urgent cases. Be sure to tell your surgeon and cardiologist about any changes in your health including symptoms of a cold or the flu. Any infection may affect your recovery.

Also, review all medications (prescription as well as over-the-counter and supplements) with your cardiologist and surgeon.

Before surgery, you may have to have an electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG), blood tests, urine tests, and a chest x-ray to give your surgeon the latest information about your health.

If you smoke, your doctor will want you to stop at least 2 weeks before your surgery. Smoking before surgery can lead to problems with blood clotting and breathing.

The night before surgery, you will be asked to bathe to reduce the amount of germs on your skin.

A medicine (anesthetic) will make you sleep during the operation. This is called “anesthesia.” Because anesthesia is safest on an empty stomach, you will be asked not to eat or drink after midnight the night before surgery. If you do eat or drink anything after midnight, it is important that you tell your anesthesiologist and surgeon.

Most patients are admitted to the hospital the day before surgery or, in some cases, on the morning of surgery.

Small metal disks called electrodes will be attached to your chest. These electrodes are connected to an electrocardiogram machine, which will monitor your heart’s rhythm and electrical activity. You will receive a local anesthetic to numb the area where a plastic tube (called a line) will be inserted in an artery in your wrist. An intravenous (IV) line will be inserted in your vein. The IV line will give you the anesthesia during the operation. You will be given something to help you relax (a mild tranquilizer) before you are taken into the operating room.

After you are completely asleep, a tube will be inserted down your windpipe and connected to a machine called a respirator, which will take over your breathing. Another tube will be inserted through your nose and down your throat, into your stomach. This tube will stop liquid and air from collecting in your stomach, so you will not feel sick and bloated when you wake up. A thin tube called a catheter will be inserted into your bladder to collect any urine produced during the operation.

A heart-lung machine is used for all valve repair or replacement surgeries. This will keep oxygen-rich blood flowing through your body while your heart is stopped. A perfusion technologist or blood-flow specialist operates the heart-lung machine. Before you are hooked up to this machine, a blood-thinning medicine called an anticoagulant will be given to prevent your blood from clotting. The surgical team is led by the cardiovascular surgeon and includes other assisting surgeons, an anesthesiologist, and surgical nurses.

After you are hooked up to the heart-lung machine, your heart is stopped and cooled. Next, a cut is made into the heart or aorta, depending on which valve is being repaired or replaced. Once the surgeon has finished the repair or replacement, the heart is then started again, and you are disconnected from the heart-lung machine.

The surgery can take anywhere from 2 to 4 hours or more, depending on the number of valves that need to be repaired or replaced.

You can expect to stay in the hospital for about a week, including at least 1 to 3 days in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU).

Recovery after valve surgery may take a long time, depending on how healthy you were before the operation. You will have to rest and limit your activities. Your doctor may want you to begin an exercise program or to join a cardiac rehabilitation program.

If you have an office job, you can usually go back to work in 4 to 6 weeks. Those who have more physically demanding jobs may need to wait longer.